Name of Rules Set by Greeks to Make Ideal Person in Art

The traditional Egyptian depiction of the torso in flat images. The figure represents the Roman Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 CE) making offerings to Egyptian Gods, Dendera Temple complex, Egypt.[1]

An creative canon of body proportions (or artful catechism of proportion), in the sphere of visual arts, is a formally codified set of criteria deemed mandatory for a particular creative fashion of figurative art. The word 'canon' (from Ancient Greek: κανών, a measuring rod or standard) was offset used for this blazon of dominion in Classical Greece, where information technology set a reference standard for body proportions, so equally to produce a harmoniously formed effigy appropriate to draw gods or kings. Other fine art styles have like rules that apply particularly to the representation of regal or divine personalities.

Ancient Egypt [edit]

Danish Egyptologist Erik Iverson determined the Canon of Proportions in classical Egyptian painting.[2] [three] This work was based on even so-detectable grid lines on tomb paintings: he adamant that the grid was 18 cells high, with the base-line at the soles of the feet and the top of the grid aligned with hair line,[4] and the navel at the eleventh line.[five] These 'cells' were specified according to the size of the subject's fist, measured across the duke.[6] (Iverson attempted to find a fixed (rather than relative) size for the grid, but this aspect of his work has been dismissed by later analysts.[7] [8]) This proportion was already established by the Narmer Palette from about the 31st century BCE, and remained in use until at least the conquest by Alexander the Great some 3,000 years afterward.[vi]

The Egyptian catechism for paintings and reliefs specified that heads should be shown in profile, that shoulders and chest be shown head-on, that hips and legs be once again in contour, and that male figures should have one foot forward and female person figures stand with anxiety together.[9]

Classical Greece [edit]

Canon of Polykleitos [edit]

In Classical Greece, the sculptor Polykleitos (fifth century BCE) established the Catechism of Polykleitos. Though his theoretical treatise is lost to history,[10] he is quoted as saying, "Perfection ... comes about little by little ( para mikron ) through many numbers".[11] By this he meant that a statue should be equanimous of conspicuously definable parts, all related to one another through a arrangement of ideal mathematical proportions and balance. Though the Kanon was probably represented by his Doryphoros, the original bronze statue has not survived, but later marble copies exist.

Despite the many advances made by modernistic scholars towards a clearer comprehension of the theoretical basis of the Catechism of Polykleitos, the results of these studies show an absence of any full general understanding upon the applied application of that canon in works of art. An ascertainment on the discipline by Rhys Carpenter remains valid:[12] "Yet it must rank equally one of the curiosities of our archaeological scholarship that no-one has thus far succeeded in extracting the recipe of the written canon from its visible apotheosis, and compiling the commensurable numbers that nosotros know it incorporates."[a]

—Richard Tobin, The Catechism of Polykleitos, 1975.[13]

Catechism of Lysippos [edit]

The sculptor Lysippos (fourth century BCE) adult a more gracile style.[14] In his Historia Naturalis , Pliny the Elder wrote that Lysippos introduced a new catechism into fine art: capita minora faciendo quam antiqui, corpora graciliora siccioraque, per qum proceritassignorum major videretur, [15] [b] signifying "a canon of actual proportions essentially different from that of Polykleitos".[17] Lysippos is credited with having established the 'eight heads high' catechism of proportion.[18]

Praxiteles [edit]

Praxiteles (fourth century BCE), sculptor of the famed Aphrodite of Knidos, is credited with having thus created a canonical course for the female nude,[xix] but neither the original work nor any of its ratios survive. Academic study of later Roman copies (and in particular modernistic restorations of them) suggest that they are artistically and anatomically inferior to the original.[20]

Classical Republic of india [edit]

The artist does not choose his own problems: he finds in the catechism didactics to make such and such images in such and such [a] way - for case, an image of Nataraja with four arms, of Brahma with iv heads, of Mahisha-Mardini with ten artillery, or Ganesa with an elephant's caput.[21]

It is in drawing from the life that a canon is probable to be a hindrance to the artist; but it is not the method of Indian fine art to piece of work from the model. Virtually the whole philosophy of Indian art is summed up in the poesy of Śukrācārya's Śukranĩtisāra which enjoins meditations upon the imager: "In order that the class of an prototype may be brought fully and clearly before the mind, the imager should medi[t]ate; and his success will exist proportionate to his meditation. No other way—non indeed seeing the object itself—will achieve his purpose." The canon then, is of use equally a rule of thumb, relieving him of some office of the technical difficulties, leaving him free to concentrate his thought more singly on the bulletin or burden of his work. It is just in this style that it must have been used in periods of great achievement, or past slap-up artists.[22]

—Ananda Chiliad. Coomaraswamy

Japan in the Heian period [edit]

Canon of Jōchō [edit]

Jōchō (定朝; died 1057 CE), too known equally Jōchō Busshi, was a Japanese sculptor of the Heian menstruation. He popularised the yosegi technique of sculpting a single effigy out of many pieces of wood, and he redefined the canon of body proportions used in Nihon to create Buddhist imagery.[23] He based the measurements on a unit equal to the altitude between the sculpted figure's chin and hairline.[24] The distance betwixt each knee joint (in the seated lotus pose) is equal to the distance from the bottoms of the legs to the pilus.[24]

Renaissance Italian republic [edit]

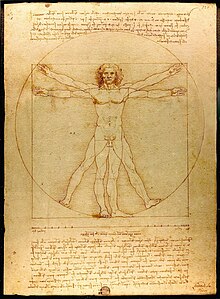

Vitruvian Homo by Leonardo da Vinci

Other such systems of 'ideal proportions' in painting and sculpture include Leonardo da Vinci'due south Vitruvian Human, based on a record of body proportions fabricated past the architect Vitruvius,[25] in the 3rd volume of his serial De architectura . Rather than setting a canon of ideal body proportions for others to follow, Vitruvius sought to place the proportions that exist in reality; da Vinci idealised these proportions in the commentary that accompanies his drawing:

The length of the outspread artillery is equal to the acme of a human being; from the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of the height of a human; from below the chin to the meridian of the head is one-eighth of the height of a man; from higher up the chest to the superlative of the head is i-6th of the elevation of a man; from above the breast to the hairline is one-seventh of the height of a man. The maximum width of the shoulders is a quarter of the height of a man; from the breasts to the top of the head is a quarter of the height of a man; the distance from the elbow to the tip of the hand is a quarter of the height of a man; the distance from the elbow to the armpit is one-eighth of the top of a homo; the length of the hand is one-tenth of the elevation of a man; the root of the penis is at half the tiptop of a man; the foot is one-seventh of the acme of a man; from below the pes to below the genu is a quarter of the height of a human; from beneath the knee to the root of the penis is a quarter of the height of a man; the distances from beneath the chin to the nose and the eyebrows and the hairline are equal to the ears and to one-third of the face.[26] [c]

Run across as well [edit]

- Academic art

- Dazzler

- Canon (basic principle), a rule or a body of rules or principles by and large established every bit valid and key in a field of art or philosophy

- Western catechism

- Nudity

- Depictions of nudity

- Nude (art)

- Neoclassicism

- Physical attractiveness

Notes [edit]

- ^ Tobin's conjectured reconstruction is described at Polykleitos#Conjectured reconstruction.

- ^ 'he made the heads of his statues smaller than the ancients, and defined the hair especially, making the bodies more slender and sinewy by which the elevation of the figure seemed greater'[16]

- ^ Translation by Wikipedia editor, copied from Vetruvian Human

References [edit]

- ^ Stadter, Philip A.; Van der Stockt, L. (2002). Sage and Emperor: Plutarch, Greek Intellectuals, and Roman Power in the Time of Trajan (98-117 A.D.). Leuven University Printing. p. 75. ISBN978-xc-5867-239-i.

Trajan was, in fact, quite agile in Arab republic of egypt. Separate scenes of Domitian and Trajan making offerings to the gods appear on reliefs on the propylon of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. There are cartouches of Domitian and Trajan on the column shafts of the Temple of Knum at Esna, and on the exterior a frieze text mentions Domitian, Trajan, and Hadrian

- ^ Erik Iversen, The myth of Egypt and its hieroglyphs in European tradition, Revue Philosophique de la France et de 50'Etranger 155 (1965), pp. 506–509.

- ^ Erik Iverson (1975). Canon and proportions in Egyptian art (2d ed.). Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

- ^ "Canon of Proportions". Pyramidofman.com.

- ^ "The Pyramid and the trunk". Pyramidofman.com.

- ^ a b Smith, W. Stevenson; Simpson, William Kelly (1998). The Art and Architecture of Aboriginal Egypt. Penguin/Yale History of Art (3rd ed.). Yale Academy Press. pp. 12–13, note 17. ISBN0300077475.

- ^ Gay Robins (2010). Proportion and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art. University of Texas Press. ISBN9780292787742.

- ^ John A.R. Legon. "The Cubit and the Egyptian Canon of Fine art". legon.demon.co.united kingdom.

- ^ Hartwig, Melinda K. (2015). A companion to Ancient Egyptian Fine art. Wiley. p. 123. ISBN9781444333503.

- ^ "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Fine art Through Time: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

we are told quite unequivocally that he related every part to every other part and to the whole and used a mathematical formula in order to do and then. What that formula was is a matter of conjecture.

- ^ Philo, Mechanicus (4.1, 49.twenty), quoted in Andrew Stewart (1990). "Polykleitos of Argos". One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works. New Haven: Yale University Press. .

- ^ Rhys Carpenter (1960). Greek Sculpture : a disquisitional review. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 100. cited in Tobin (1975)

- ^ Tobin, Richard (1975). "The Catechism of Polykleitos". American Periodical of Archæology. 79 (4): 307–321. doi:10.2307/503064. JSTOR 503064. Retrieved ii October 2020.

- ^ Charles Waldstein, PhD. (December 17, 1879). Praxiteles and the Hermes with the Dionysos-kid from the Heraion in Olympia (PDF). p. 18.

The canon of Polykleitos was heavy and square, his statues were quadrata signa , the catechism of Lysippos was more slim, less fleshy

- ^ Pliny the Elder. "XXXIV 65". Historia Naturalis . cited in Waldstein (1879)

- ^ George Redford, FRCS. "Lysippos and Macedonian Art". A transmission of ancient sculpture: Egyptian–Assyrian–Greek–Roman (PDF). p. 193.

- ^ Walter Woodburn Hyde (1921). Olympic Victor Monuments and Greek Athletic Art. Washington: the Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 136.

- ^ "Hercules: The influence of works past Lysippos". Paris: The Louvre. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

In the fourth century BCE, Lysippos drew up a canon of proportions for a more elongated figure that that defined by Polykleitos in the previous century. According to Lysippos, the meridian of the head should be ane-eighth the height of the torso, and not ane-seventh, equally Polykleitos recommended.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (1996). "The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and the Product of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient Art". Oxford Art Periodical. 19 (ii): four. JSTOR 1360725. Retrieved four April 2021.

- ^ Ad. Michaelis (1887). "The Cnidian Aphrodite of Praxiteles". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 8: 324–355. doi:10.2307/623481. hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t4nk9qk9q. JSTOR 623481. Retrieved v April 2021.

- ^ Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1911). "Indian Images with Many Arms". The Trip the light fantastic toe of Shiva – fourteen Indian essays.

- ^ Ananda Coomaraswamy (1934). "Artful of The Śukranĩtisāra". The Transformation of Nature in Fine art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 111–117. cited in Mosteller, John F (1988). "The Study of Indian Iconometry in Historical Perspective". Periodical of the American Oriental Order. 108 (ane): 99–110. doi:x.2307/603249. JSTOR 603249. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Miyeko Murase (1975). Japanese art : selections from the Mary and Jackson Burke Collection. New York, Northward.Y.: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 22. ISBN9780870991363.

- ^ a b Mason, Penelope; Dinwiddie, Donald (2005). History of Japanese Art (2nd. ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 144. ISBN9780131176010.

- ^ Vitruvius. "I, "On Symmetry: In Temples And In The Human Body"". X Books on Architecture, Book III. Translated by Morris Hicky Morgan. Harvard University Printing. Retrieved 15 October 2020 – via Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci. "Human proportions". The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Translated by Edward MacCurdy. Raynal and Hitchcock Inc. p. 213–214 – via Archive.org.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions

0 Response to "Name of Rules Set by Greeks to Make Ideal Person in Art"

Post a Comment